Dr. W.C Minor was a surgeon assigned to the American Airforce during the American Civil War, and at some point in his career he was forced to brand an Irishman who abandoned the army. The act of branding this man was to haunt him for the rest of his life and he had a terrible fear that Irishmen were out to get him. Ofcourse, the fact that he had paranoid schizophrenia (known as monomania in those days) only compounded the issue and one night, imagining that someone was out to get him, he shot and killed a certain innocent George Merrett in England which is when he was declared insane and put away in a mental asylum in Broadmoor, UK. He was only 37 years old.

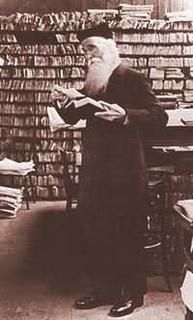

When he was back to his lucid self and realized what he had done, he was full of remorse and insisted on sending Merrett's widow and seven small children, money as compensation. Seven years after Merrett's death his widow infact forgave him and even visited him in his suite/cell bringing him books that he had ordered from antiquarian dealers in London. It is through one of those books that he saw a flyer by one Dr. James Murray, of the London Philological society, requesting contributions in the form of quotes, from the public towards the gargantuan project, the making of the Oxford English Dictionary. The OED project was both ambitious and unique since it not only defined words, but also traced the history of words through quotations obtained from literature and non-fiction. It was initially expected to take 10 years with four volumes, but it turned out to be 70 years and it was 12 volumes!

Minor decided that a project such as this might help his psychosis and his diligence as a contributor resulted in his being responsible for something like 10,000 words in the final OED. Dr. James Murray was very impressed with Minor's contributions and wrote to him often requesting a meeting little realizing that his chief contributor was infact an inmate in a mental asylum. When they did meet however, it was to spark a genuine and wonderful friendship that spanned many decades. The relationship seemed all the more unique because the men came from such different backgrounds: Murray was poor, the son of a tailor, a self-educated Scotsman who spoke 25 languages and was a pious Congregationalist; Minor was a wealthy, aristocratic American, educated at Yale, a surgeon during the Civil War, an agnostic and libertine. But both were brought together by a love of books and langague. Infact, it was due to Murray's intense campaining for his friend that resulted in WC Minor being transferred back to the US to spend his remaining days in the country of his birth.

Simon Winchester, I think, does a brilliant job on this book. He is a wonderful story-teller and uses impeccable Victorian English which draws you in until you feel like you are a part of the coterie of those wise and literary old men.

In particular, in telling Dr. Minor's story, Simon Winchester, using a whole host of anecdotes from Minor's life, manages to describe a very disturbed, and at the same time, an altogether decent human character. By taking us back to Dr. Minor's childhood in Ceylon we are shown how his strict missionary upbringing might have fostered terrible feelings of guilt in him with regard to sex, so much so, that this poor disturbed man actually cut off his penis 'to appease the deities'. You want to cry for such a brilliant scholarly mind that is so consumed with paranoia. It makes you want to scream that in those times there was no medication for schizophrenia, but then again, as Winchester muses, "if he had been treated with mood-altering sedatives, as they would have done in Edwardian times, or treating him as today with such antipshycotic drugs as quetiapine or risperidone, many of his symptoms of madness might have gone away-but he might well have felt disinclined or unable to perform his work for Dr. Murray.." In other words, the burning question is: would we had such a brilliant contribution from him if it wasn't for his madness?

The third protagonist of the book (if I can call it that) is the dictionary itself. To read about the several eccentric personalities that were involved with the dictionary's creation weaves a sparkling tale. Dr. James Murray was the primary editor, but there were a lot of other notable people involved including, Henry Liddell (whose daughter Alice has so captivated the Christ Church mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson that he wrote an adventure book for her, set in Wonderland), Max Mueller, the Leipzig philologist and Oriental scholar, William Stubbs and even a young J.R.R. Tolkien, worked on words beginning with "W" and labored intensely over the history of the word walrus. I especially loved how the author chose some of the most elegant entries from the OED to use as epigrams for each chapter for eg., "polymath", "philology", "sesquipedalian", etc.

All in all this is a wonderful book guaranteed to leave you with a new found appreciation for your common dictionary in general and the OED in your library in particular.