"...when an auspicious day has been chosen, the corpse is carried on the back of a special bearer to the sky burial altar. Lamas come from the local monastery to send the spirit on its way and, as they chant the scriptures that release the soul from purgatory, the sky burial master blows a horn, lights the mulberry fire to summon the vultures, and dismembers the body, smashing the bones in an order prescribed by ritual. The body is dismembered in different ways, according to the cause of death, but, whichever way is chosen, the knife work must be flawless, otherwise demons will come to steal the spirit..."

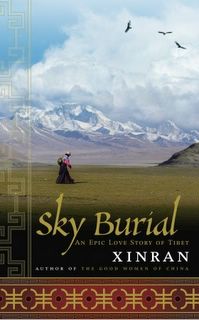

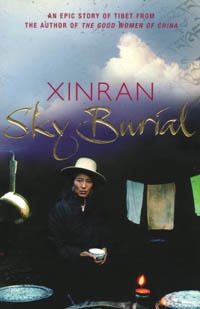

Think you're reading a passage from a recent mystery or thriller novel? No, the passage is from Xinran's latest offering, a book titled "Sky Burial" and the passage is describing the title of the novel. A sky burial is a Tibetan riutal for the dead and non-Tibetans are not permitted to partake in it. So, when as a young girl in China, Xinran heard a rumour about a Chinese soldier in Tibet who had been fed to the vultures in this ritual, the tale both frightened and fascinated her. Several decades later Xinran met Shu Wen, a Chinese woman in Suzhou who had spent years searching for her missing husband Kejun, after he disappeared in Tibet. Their story would help unravel the legend of the Sky Burial.

Xinran met Shu Wen in 1994: “An old woman dressed in Tibetan clothing, smelling strongly of old leather, rancid milk and animal dung. Her grey hair hung in two untidy plaits, and her skin was lined and weather–beaten. Yet...her accent immediately confirmed to me that she was indeed Chinese.”

Shu Wen was a dermatologist and shortly after she married her surgeon sweetheart Kejun he elected to join the Chinese Army and travel to Tibet to care for the wounded Chinese soldiers there (this was in 1958 after mao sent in the Chinese army to Tibet on account of the growing strength of the Tibetan Independence Movement supported by the Dalai Lama). After 6 months she was informed by the Chinese government that Kejun had passed away but they didn't say when or how. With these questions left unanswered she found it very difficult to carry on with her life and vowed that she would travel to Tibet (she, too, would join the Chinese army) to find out if her husband was dead or alive.

Shortly after her arrival in Tibet she is separated from her contingent of Chinese soldiers during a skirmish and her only companion is a Tibetan woman named Zhuoma, who was rescued earlier by the Chinese soldiers. Zhuoma was an ideal companion because being Tibetan not only could she act as a guide to Wen, but she too was on a mission to find her lover. Cold, tired and hungry Shu Wen and Zhuoma are given shelter by a nomadic Tibetan family and she spends the next 30 or so years with them while continuing to look for Kejun and not having much luck.

It is through the lives of this nomadic family that the author Xinran shares with us the unique culture of the Tibetan people and how their everyday lives are so connected to the spiritual, so intertwined with Buddhism. Where prayer wheels, mani stones (boulders engraved with pictures and prayers), mantras (prayerful chants), Buddhist monastaries and lamas color the landscape just like cars and fancy buildings would color our scenery.

Their isolation from the rest of the world is also something to be amazed at...this was a land where where half a lead pencil was a monastery's most prized (and modern) possession, where people spent years looking for one another, weeks crossing a single mountain pass, where farmers sow their seeds and simply leave the fate of their crops to the heavens because there are no modern farming techniques.

Shu Wen spent close to 30 years in Tibet looking for her lost husband and because Tibet is so isolated from the rest of the world, she found that when she returned to China she missed the start and end of the Cultural Revolution in the '70's and Deng Xiaoping's "reform and opening" of the '80's The China she returns to is no longer identifyable as the China she left, and she also realized that she was also no longer staunchly Chinese as she once was---it is clear she left her heart in Tibet.

In conclusion, this novel is unique not just because of its story but also because it is rare to have the opportunity to see Tibet as it was in the 1950's through the eyes of a Chinese author and protagonist. If I do have a quibble with Xinran it would be over how she chose to portray the Chinese soldiers. She made them all out to be very courteous and soft-spoken towards the Tibetans when history has shown us that just the opposite is true. Anyway, the book has sparked a desire in me to learn more about Tibet, so much so I have picked as my next read, Patrick French's, "Tibet, Tibet".